Jenifer Elmslie

Policymakers are increasingly under pressure to move beyond climate commitments to tangible climate policy and the aviation sector is no exception with policymakers trying to balance economic, social, political and environment factors as they shape the policy which will drive the sector to net-zero by 2050.

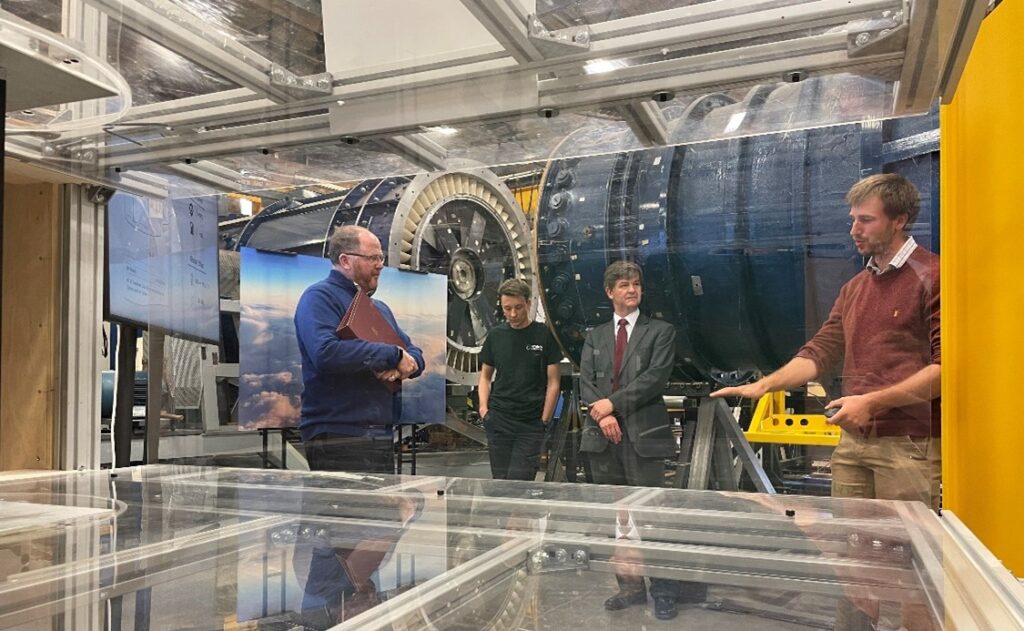

Last month, Sir Patrick Vallance, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK government and the Go Science team visited the Whittle Lab, home of the Aviation Impact Accelerator (AIA), to hear about how the AIA’s whole system modelling tools can help find pathways to sustainable flight. This visit was followed by a workshop with the Department for Transport (DfT) Advanced Fuels team and a meeting with George Freeman MP, Minister for Science, Research and Innovation.

During these visits, the AIA team’s aim was to help these key stakeholders to better visualise the possible futures of the policy decisions which drive technology development and economic behaviour. The AIA’s mission is to accelerate the journey to sustainable aviation by developing evidence-based tools that allow people to map, understand, and embark on the pathways towards sustainable flight. Now is an exciting point for the initiative, where the team can take the tools developed over the past two years and help stakeholders to visualise the whole system, confront uncertainty, explore trade-offs, and identify opportunities.

How has the UK government committed to make aviation greener?

The UK Government has shown serious ambition in recent commitments, with a growing set of policy discussions and strategy around aviation.

The Department for Transport’s 2020 Decarbonising Transport paper laid out new targets for the aviation to reach net zero aviation by 2040, 10 years ahead of previous plans. April 2021’s sixth Carbon Budget committed the government to cut emissions from domestic aviation by 78% by 2035, as well as incorporating the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping emissions for the first time.

In the race towards the deployment of sustainable fuels, the Prime Minister’s 2020 10 Point Plan for a green industrial revolution committed to ramping up the supply of sustainable aviation fuels or SAFs by 2025. This government commitment would mandate the replacement of 10% of fossil jet fuel by SAF by the year 2030. Building on the 10 Point Plan, the government confirmed its ambition for supporting its support of the UK SAF industry with £180 million for their development through the 2021 Net Zero Strategy. The Net Zero strategy also promised £150 million per year of investment to the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI) to support the development of greener aircraft technology, including hydrogen-propulsion systems. This was accompanied by ambition to increase hydrogen production, although with an unclear timeline between ambition and production.

In March 2022 the Government went even further, announcing an extra £685 million of funding over the next 3 years to the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI) programme, an increase of more than 50% in funding from the previous 3-year period, in addition to its Net Zero commitments. Industry will provide co-funding, taking the total amount to support the development of zero-carbon and ultra-low-emission aircraft technology to over £1 billion.

Further to this, the government’s Jet Zero strategy outlined plans to accelerate the race to sustainable aviation, focusing mostly on the efficiency of the aviation system and using market influence to drive down emissions, including influencing consumer behaviour.

The UK Government’s various commitments have proven that, across government departments, there is a commitment to using policy to speed up the net zero transition in aviation, and its appetite for ambition. However, there is no silver bullet in terms of policy or technology and a great deal of uncertainty remains across the whole aviation system and its future.

Policy and technical uncertainties: How can the AIA’s modelling help?

Aviation is a particularly difficult sector to decarbonise, with its technical constraints, stringent safety regulations and highly siloed key players, leading to many challenges for transitioning the whole sector.

The sector is made up by fuel producers and distributors, aircraft manufacturers, aircraft leasers, airports, airlines and many more players. All these organisations must work together to transition away from burning fossil fuels and policy makers must help to lead the way.

There are four main technology routes to reducing the climate impact of aviation: Sustainable Aviation Fuels (bio-based and synthetic), hydrogen combustion aircraft, hydrogen fuel cell aircraft and battery electric aircraft, and each have their own opportunities, challenges, and synergies. There are also operational changes and efficiency improvements which could reduce the climate impact of aviation. A final potential lever to reduce the climate is demand-side management

The government faces a huge challenge in forming new policy against the backdrop of uncertain technology options, fuel production scale-up and distribution, cost and overall impact on the climate, not to mention the competition with other sectors for the resources, such as renewable energy, required for decarbonisation.

Appetite for SAFs is high amongst airframe manufacturers, air liners, airports and consumers because it is a “drop-in” fuel: it can be blended with current fossil jet fuel, burnt in current aircraft and could theoretically start reducing the impact of in-flight CO2 emissions right away. However, there is a high level of uncertainty around the different types of SAF, their scale-up and their wider environmental impacts. Before the pandemic, the cost of producing biofuel-based SAF was 2-3 times the 2019 price of jet fuel. However, today’s dominant SAF, made from used cooking oils and waste fats, has enough feedstock only to provide around 5% of the world’s jet fuel consumption. In the future, synthetic SAFs made from electricity, water and carbon captured from the atmosphere or from biomass, can overcome the challenge of feedstock availability. However, the cost of these fuels in 2050 is projected to be 3-10 times higher than 2019’s price of jet fuel, depending on electricity cost and technology maturity in the future. Additionally, the electricity required to meet 2050’s jet fuel demand via synthetic routes can be more than 50% of current global electricity production. Meanwhile, technologies like battery electric and hydrogen-based aircraft, are years from market use at scale and also have significant uncertainties remaining around range potential, hydrogen production, storage and distribution and battery management.

‘Flying is our safest, fastest, and lowest cost mode of transport but today it has unsustainable consequences for our planet. Most of us are aware of the effect of aviation’s CO2 emissions but other combustion products including NOx, soot, and water vapor have an even larger impact on climate change. It is essential that we cease development of aircraft that burn fuel in the upper atmosphere’

JoeBen Bevirt, CEO – Joby Aviation, AIA roundtable, 2022

A further significant uncertainty for the future of aviation is the warming effects of non-CO2 aircraft emissions, such as contrails and nitrogen oxides (NOx). Although the global aviation industry contributes to roughly 2-3% of global annual CO2 emissions, incorporating non-carbon emissions would give a much fuller picture of the problem and doubles this estimate. Condensation trails or ‘contrails’ are more insidious than they appear; once their heating impact is included, researchers from Yale estimate that aircrafts cause 5% of anthropogenic warming. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are also understood to contribute to a net warming effect, increasing the levels of ozone and decreasing atmospheric ambient methane, with little known about their effect.

The UK government’s 2021 consultation only dedicated a single page to discuss the impact of non-CO2 emissions, mentioning the net-positive impacts that SAF will have on reducing non-CO2 impacts. The consultation included little in the way of ambitious leading policy to address contrails. Indeed, no country legislates for the non-CO2 warming effects that flying causes.

The complexity is great and the timescale it short, industry and policymakers have limited time to make decisions which will play out for years to come and ultimately decide if the aviation sector will reach net-zero. The AIA’s whole-system model, focused from resource inputs all the way to climate impact is key to cutting through this complexity, it can help policymakers to see the whole aviation system and how it connects to other sectors. The model allows decision-makers to move beyond climate commitments to understand the opportunities, challenges and uncertainty of potential pathways and ultimately make decisions which prioritise people, nature and climate.

‘The AIA’s model helps key players make informed investment and policy making decisions by helping them to visualise the impact of future decisions.’

Chris Raymond, Chief Sustainability Officer – Boeing, AIA Roundtable, 2022

Opportunities for the UK

The UK has a long history of aviation innovation. The Whittle Laboratory, home of the AIA, has its origins in Sir Frank Whittle and a number of his original team, from Cambridge, and who in 1937 invented the jet engine. The UK is home to many research institutions, incumbent, and new companies with the potential to help lead the sector towards sustainability. With the right Governmental leadership and support, this potential could be unleashed and bring the UK to the forefront of aviation research.

As passenger travel rises to pre-pandemic levels, some estimates suggest that emissions could triple in the next three decades. The current moment serves as an opportunity for allow the UK Government to rebuild a better aviation sector and make the UK a leader in achieving net zero aviation, including showing true leadership around technical innovation and addressing the non-CO2 effects like contrails and NOx.

Recent visits to the Whittle Lab by the chief government scientific advisor, an expert team from the Department for Transport, and representative from the House of Commons and BEIS marks the start of the AIA engagement with policymakers. The AIA will be building on this engagement with UK policy makers to explore policy scenarios in the UK and globally and accelerate change.

“I was hugely impressed to see for myself the leading role the Whittle Laboratory at the University of Cambridge is playing in ensuring the UK leads in the race to net zero fight. Their Aviation Impact Accelerator model has the potential to be a game-changing tool to accelerate us in this race and ensure policy and innovation decisions have real impact”

Geroge Freeman MP, Minister for Science, Research and Innovation, UK Government

Jenifer is on the Policy and Business team at the Aviation Impact Accelerator, and is based at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership.